Sunday, April 24, 2011

Education: The PhD factory

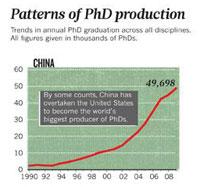

Scientists who attain a PhD are rightly proud — they have gained entry to an academic elite. But it is not as elite as it once was. The number of science doctorates earned each year grew by nearly 40% between 1998 and 2008, to some 34,000, in countries that are members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). The growth shows no sign of slowing: most countries are building up their higher-education systems because they see educated workers as a key to economic growth (see 'The rise of doctorates'). But in much of the world, science PhD graduates may never get a chance to take full advantage of their qualifications.

Click for larger version.

Click for larger version.In some countries, including the United States and Japan, people who have trained at great length and expense to be researchers confront a dwindling number of academic jobs, and an industrial sector unable to take up the slack. Supply has outstripped demand and, although few PhD holders end up unemployed, it is not clear that spending years securing this high-level qualification is worth it for a job as, for example, a high-school teacher. In other countries, such as China and India, the economies are developing fast enough to use all the PhDs they can crank out, and more — but the quality of the graduates is not consistent. Only a few nations, including Germany, are successfully tackling the problem by redefining the PhD as training for high-level positions in careers outside academia. Here, Nature examines graduate-education systems in various states of health.

Japan: A system in crisis

Of all the countries in which to graduate with a science PhD, Japan is arguably one of the worst. In the 1990s, the government set a policy to triple the number of postdocs to 10,000, and stepped up PhD recruitment to meet that goal. The policy was meant to bring Japan's science capacity up to match that of the West — but is now much criticized because, although it quickly succeeded, it gave little thought to where all those postdocs were going to end up.

Academia doesn't want them: the number of 18-year-olds entering higher education has been dropping, so universities don't need the staff. Neither does Japanese industry, which has traditionally preferred young, fresh bachelor's graduates who can be trained on the job. The science and education ministry couldn't even sell them off when, in 2009, it started offering companies around ¥4 million (US$47,000) each to take on some of the country's 18,000 unemployed postdoctoral students (one of several initiatives that have been introduced to improve the situation). "It's just hard to find a match" between postdoc and company, says Koichi Kitazawa, the head of the Japan Science and Technology Agency.

This means there are few jobs for the current crop of PhDs. Of the 1,350 people awarded doctorates in natural sciences in 2010, just over half (746) had full-time posts lined up by the time they graduated. But only 162 were in the academic sciences or technological services,; of the rest, 250 took industry positions, 256 went into education and 38 got government jobs.

Click for larger version.

Click for larger version.With such dismal prospects, the number entering PhD programmes has dropped off (see 'Patterns of PhD production'). "Everyone tends to look at the future of the PhD labour market very pessimistically," says Kobayashi Shinichi, a specialist in science and technology workforce issues at the Research Center for University Studies at Tsukuba University.

China: Quantity outweighs quality?

The number of PhD holders in China is going through the roof, with some 50,000 people graduating with doctorates across all disciplines in 2009 — and by some counts it now surpasses all other countries. The main problem is the low quality of many graduates.

Yongdi Zhou, a cognitive neuroscientist at the East China Normal University in Shanghai, identifies four contributing factors. The length of PhD training, at three years, is too short, many PhD supervisors are not well qualified, the system lacks quality control and there is no clear mechanism for weeding out poor students.

Even so, most Chinese PhD holders can find a job at home: China's booming economy and capacity building has absorbed them into the workforce. "Relatively speaking, it is a lot easier to find a position in academia in China compared with the United States," says Yigong Shi, a structural biologist at Tsinghua University in Beijing, and the same is true in industry. But PhD graduates can run into problems if they want to enter internationally competitive academia. To get a coveted post at a top university or research institution requires training, such as a postdoctoral position, in another country. Many researchers do not return to China, draining away the cream of the country's crop.

The quality issue should be helped by China's efforts to recruit more scholars from abroad. Shi says that more institutions are now starting to introduce thesis committees and rotations, which will make students less dependent on a single supervisor in a hierarchical system. "Major initiatives are being implemented in various graduate programmes throughout China," he says. "China is constantly going through transformations."

Singapore: Growth in all directions

The picture is much rosier in Singapore. Here, the past few years have seen major investment and expansion in the university system and in science and technology infrastructure, including the foundation of two new publicly funded universities. This has attracted students from at home and abroad. Enrolment of Singaporean nationals in PhD programmes has grown by 60% over the past five years, to 789 in all disciplines — and the country has actively recruited foreign graduate students from China, India, Iran, Turkey, eastern Europe and farther afield.

“Everyone tends to look at the future of the PhD labour market very pessimistically.”

Because the university system in Singapore has been underdeveloped until now, most PhD holders go to work outside academia, but continued expansion of the universities could create more opportunities. "Not all end up earning a living from what they have been trained in," says Peter Ng, who studies biodiversity at the National University of Singapore. "Some have very different jobs — from teachers to bankers. But they all get a good job." A PhD can be lucrative, says Ng, with a graduate earning at least S$4,000 (US$3,174) a month, compared with the S$3,000 a month earned by a student with a good undergraduate degree.

"I see a PhD not just as the mastery of a discipline, but also training of the mind," says Ng. "If they later practise what they have mastered — excellent — otherwise, they can take their skill sets into a new domain and add value to it."

United States: Supply versus demand

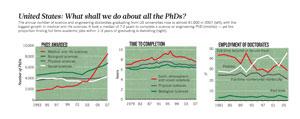

To Paula Stephan, an economist at Georgia State University in Atlanta who studies PhD trends, it is "scandalous" that US politicians continue to speak of a PhD shortage. The United States is second only to China in awarding science doctorates — it produced an estimated 19,733 in the life sciences and physical sciences in 2009 — and production is going up. But Stephan says that no one should applaud this trend, "unless Congress wants to put money into creating jobs for these people rather than just creating supply".

Click for larger version.

Click for larger version.The proportion of people with science PhDs who get tenured academic positions in the sciences has been dropping steadily and industry has not fully absorbed the slack. The problem is most acute in the life sciences, in which the pace of PhD growth is biggest, yet pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries have been drastically downsizing in recent years. In 1973, 55% of US doctorates in the biological sciences secured tenure-track positions within six years of completing their PhDs, and only 2% were in a postdoc or other untenured academic position. By 2006, only 15% were in tenured positions six years after graduating, with 18% untenured (see 'What shall we do about all the PhDs?'). Figures suggest that more doctorates are taking jobs that do not require a PhD. "It's a waste of resources," says Stephan. "We're spending a lot of money training these students and then they go out and get jobs that they're not well matched for."

The poor job market has discouraged some potential students from embarking on science PhDs, says Hal Salzman, a professor of public policy at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, New Jersey. Nevertheless, production of US doctorates continues apace, fuelled by an influx of foreign students. Academic research was still the top career choice in a 2010 survey of 30,000 science and engineering PhD students and postdocs, says Henry Sauermann, who studies strategic management at the Georgia Institute of Technology in Atlanta. Many PhD courses train students specifically for that goal. Half of all science and engineering PhD recipients graduating in 2007 had spent over seven years working on their degrees, and more than one-third of candidates never finish at all.

Some universities are now experimenting with PhD programmes that better prepare graduate students for careers outside academia (see page 280). Anne Carpenter, a cellular biologist at the Broad Institute of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, is trying to create jobs for existing PhD holders, while discouraging new ones. When she set up her lab four years ago, Carpenter hired experienced staff scientists on permanent contracts instead of the usual mix of temporary postdocs and graduate students. "The whole pyramid scheme of science made little sense to me," says Carpenter. "I couldn't in good conscience churn out a hundred graduate students and postdocs in my career."

But Carpenter has struggled to justify the cost of her staff to grant-review panels. "How do I compete with laboratories that hire postdocs for $40,000 instead of a scientist for $80,000?" she asks. Although she remains committed to her ideals, she says that she will be more open to hiring postdocs in the future.

Germany: The progressive PhD

Germany is Europe's biggest producer of doctoral graduates, turning out some 7,000 science PhDs in 2005. After a major redesign of its doctoral education programmes over the past 20 years, the country is also well on its way to solving the oversupply problem.

Traditionally, supervisors recruited PhD students informally and trained them to follow in their academic footsteps, with little oversight from the university or research institution. But as in the rest of Europe, the number of academic positions available to graduates in Germany has remained stable or fallen. So these days, a PhD in Germany is often marketed as advanced training not only for academia — a career path pursued by the best of the best — but also for the wider workforce.

“The relatively low income of german academic staff makes leaving the university after the PhD a good option.”

Universities now play a more formal role in student recruitment and development, and many students follow structured courses outside the lab, including classes in presenting, report writing and other transferable skills. Just under 6% of PhD graduates in science eventually go into full-time academic positions, and most will find research jobs in industry, says Thorsten Wilhelmy, who studies doctoral education for the German Council of Science and Humanities in Cologne. "The long way to professorship in Germany and the relatively low income of German academic staff makes leaving the university after the PhD a good option," he says.

Thomas Jørgensen, who heads a programme to support and develop doctoral education for the European University Association, based in Brussels, is concerned that German institutions could push reforms too far, leaving students spending so long in classes that they lack time to do research for their thesis and develop critical-thinking skills. The number of German doctorates has stagnated over the past two decades, and Jørgensen worries about this at a time when PhD production is growing in China, India and other increasingly powerful economies.

Poland: Expansion at a cost

Growth in PhD numbers among Europe's old guard might be waning, but some of the former Eastern bloc countries, such as Poland, have seen dramatic increases. In 1990–91, Polish institutions enrolled 2,695 PhD students. This figure rose to more than 32,000 in 2008–09 as the Polish government, trying to expand the higher-education system after the fall of Communism, introduced policies to reward institutions for enrolling doctoral candidates.

Despite the growth, there are problems. A dearth of funding for doctoral studies causes high drop-out rates, says Andrzej Kraśniewski, a researcher at Warsaw University of Technology and secretary-general of the Polish Rectors Conference, an association representing Polish universities. In engineering, more than half of students will not complete their PhDs, he says. The country's economic growth has not kept pace with that of its PhD numbers, so people with doctorates can end up taking jobs below their level of expertise. And Poland needs to collect data showing that PhDs from its institutions across the country are of consistent quality, and are comparable with the rest of Europe, says Kraśniewski.

Click for larger version.

Click for larger version.Still, in Poland as in most countries, unemployment for PhD holders is below 3%. "Employment prospects for holders of doctorates remain better than for other higher-education graduates," says Laudeline Auriol, author of an OECD report on doctorate holders between 1990 and 2006, who is now analysing doctoral-student data up to 2010. Still, a survey of scientists by Nature last year showed that PhD holders were not always more satisfied with their jobs than those without the degree, nor were they earning substantially more (see 'What's a PhD worth?').

Egypt: Struggle to survive

Egypt is the Middle East's powerhouse for doctoral studies. In 2009, the country had about 35,000 students enrolled in doctoral programmes, up from 17,663 in 1998. But funding has not kept up with demand. The majority comes through university budgets, which are already strained by the large enrolment of students in undergraduate programmes and postgraduate studies other than PhDs. Universities have started turning to international funding and collaborations with the private sector, but this source of funding remains very limited.

The deficit translates into shortages in equipment and materials, a lack of qualified teaching staff and poor compensation for researchers. It also means that more of the funding burden is falling on the students. The squeeze takes a toll on the quality of research, and creates tension between students and supervisors. "The PhD student here in Egypt faces numerous problems," says Mounir Hana, a food scientist and PhD supervisor at Minia University, who says that he tries to help solve them. "Unfortunately, many supervisors do not bother, and end up adding one more hurdle in the student's way."

Graduates face a tough slog. As elsewhere, there are many more PhD holders in Egypt than the universities can employ as researchers and academics. The doctorate is frequently a means of climbing the civil-service hierarchy, but those in the private sector often complain that graduates are untrained in the practical skills they need, such as proposal writing and project management. Egyptian PhD holders also struggle to secure international research positions. Hana calls the overall quality of their research papers "mediocre" and says that pursuing a PhD is "worthless" except for those already working in a university. But the political upheaval in the region this year could bring about change: many academics who had left Egypt are returning, hoping to help rebuild and overhaul education and research.

Few PhDs are trained elsewhere in the Middle East — less than 50 a year in Lebanon, for example. But several world-class universities established in the oil-rich Gulf States in recent years have increased demand for PhD holders. So far, most of the researchers have been 'imported' after receiving their degrees from Western universities, but Saudi Arabia and Qatar in particular have been building up their infrastructure to start offering more PhD programmes themselves. The effect will be felt throughout the region, says Fatma Hammad, an endocrinologist and PhD supervisor at Al-Azhar University in Cairo. "Many graduates are now turning to doctoral studies because there is a large demand in the Gulf States. For them, it is a way to land jobs there and increase their income," she says.

India: PhDs wanted

In 2004, India produced around 5,900 science, technology and engineering PhDs, a figure that has now grown to some 8,900 a year. This is still a fraction of the number from China and the United States, and the country wants many more, to match the explosive growth of its economy and population. The government is making major investments in research and higher education — including a one-third increase in the higher-education budget in 2011–12 — and is trying to attract investment from foreign universities. The hope is that up to 20,000 PhDs will graduate each year by 2020, says Thirumalachari Ramasami, the Indian government's head of science and technology.

Those targets ought to be easy to reach: India's population is young, and undergraduate education is booming (see Nature 472, 24–26; 2011). But there is little incentive to continue into a lengthy PhD programme, and only around 1% of undergraduates currently do so. Most are intent on securing jobs in industry, which require only an undergraduate degree and are much more lucrative than the public-sector academic and research jobs that need postgraduate education. Students "don't think of PhDs now, not even master's — a bachelor's is good enough to get a job", says Amit Patra, an engineer at the Indian Institute of Technology in Kharagpur.

Even after a PhD, there are few academic opportunities in India, and better-paid industry jobs are the major draw. "There is a shortage of PhDs and we have to compete with industry for that resource — the universities have very little chance of winning that game," says Patra. For many young people intent on postgraduate education, the goal is frequently to go to the United States or Europe. That was the course chosen by Manu Prakash, who went to MIT for his PhD and now runs his own experimental biophysics lab at Stanford University in California. "When I went through the system in India, the platform for doing long-term research I didn't feel was well-supported," he says.

Source: nature.com

by David Cyranoski , Natasha Gilbert , Heidi Ledford , Anjali Nayar & Mohammed Yahia

Subscribe to Comments [Atom]